BETWEEN A GUN AND A DRY PLACE: WILDLIFE AT RISK FROM DROUGHT AND HUMAN CONFLICT IN MEXICO

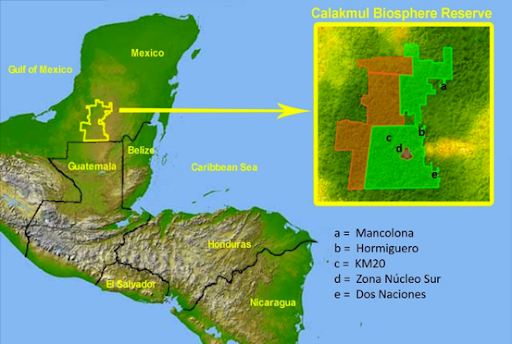

In Calakmul Mayan Biosphere Reserve, Mexico, climate change is upsetting an ancient balance between indigenous Mayan people and the Yucatan’s wildlife. Animal populations are migrating under pressure from drought, and some species are being pushed into conflict with humans. Large Mammal Scientist Raphael Coleman reports from a 2017 expedition.Calakmul is located in the South of the Yucatan peninsula, just above the Mexico-Guatemala border. With its links to surrounding reserves and wilderness areas, it forms part of the largest continuous area of forest in the Americas after the Amazon itself. As a result, its home to a great variety of plant species and wild animals – from toucans and trogons to tapirs and jaguars. around 20 000 people, mostly indigenous Mayans, live in the buffer zone of the park and the transition area surrounding that – and all have to make a living.

A drought that kills

In Calakmul, the soil is porous and water drains quickly into the ground. In recent years, this has been coupled with a worsening problem – climate change is altering the landscape. The only water sources in the core zone of the reserve are aguadas, rain-fed ponds that are drying up fast after five years of drought. Even large previously permanent aguadas are disappearing. All that’s left is a shrinking hole in the forest, with vegetation growing into it like scar tissue closing a wound.

So many species depend on the aguadas that their disappearance could trigger catastrophic loss of biodiversity. If rain doesn’t replenish the water, amphibians can’t disperse far. Aguadas are also havens for many reptiles, such as mud turtles and Morelet’s crocodiles (see Box 1). More mobile animals such as birds and mammals are forced to use behavioural adaptation, dispersing farther afield to find drinking water.

A movement study of white-lipped peccary a threatened wild boar species showed they adapt the size of their home ranges seasonally in Calakmul. While they roam further in the wet season, in the dry season they restrict their movements to a safe distance from a reliable water source. But when aguada Calakmul, one of the biggest in the reserve, dried up completely in 2006, the peccary groups living around it were in trouble. Those that remained suffered in the absence of water, with camera traps revealing them to be in poor health – and many didn’t survive the drought. However, some groups migrated over 15km south to find water.

Human-wildlife conflict begins when mammals such as peccary, deer and tapir venture into the buffer zones. Permanent water sources such as rivers are often settled by people and, outside the reserve, hunting many species is legal for indigenous locals. Herds of peccary can ruin an entire crop of maize or beans. Thirsty tapir destroy beehives as they rampage through apiaries to drink from water troughs farmers leave out for the bees. Considering these problems, it is understandable that local Mayans often return to a practice that is a part of their cultural heritage-hunting. Deer, peccary and tapir alter their behaviour in hunted areas, living in flooded forests more to avoid humans compared with non-hunted regions of Calakmul.

Predators like puma and jaguar follow the prey and the water, but if human hunters have depleted their prey, the predators have to find other ways to survive. As the drought progresses and prey species migrate south (Fige), locals have reported an increase in the number of predator attacks on their livestock. If hungry and desperate, ocelot – a wild cat native to South America – will sneak into villages and snatch chickens. Several locals described seeing jaguar take down goats. If a puma gets into a farmer’s paddock, it may kill everything it can catch, much like a fox in a chicken coop. For people living in the buffer zone and transition area on the edge of the reserve, the main source of income and food is small-scale farming, so losing crops and livestock hits them hard.

When you ask locals living around the reserve whether they still hunt, or whether they’ve had problems with predators attacking their livestock, many become guarded and tense. They all say they would never hunt jaguar or tapir, both species known to be internationally protected and vulnerable to extinction. Eventually, interviews revealed that deer, peccary, paca and curassow are commonly targeted. The locals often believed that the species they had shot wasn’t protected, or that their hunts were outside the reserve boundaries.

One of the Mayan tracking guides told of how his family had once bought “venison” from a hunter. When questioned about the taste and texture, the hunter admitted to bringing down a tapir with a shotgun – a strictly illegal kill as the species (Tapirus bairdii) is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of threatened species.

Tackling the conflict

Evaluating how human activity impacts wildlife populations, and addressing threats through conservation action, is a complicated business. This is where Operation Wallacea (known as “OpWall”) comes in. Every year since 2012, OpWall’s Mexico expeditions have led dozens of scientists and hundreds of students deep into Calakmul’s jungles, conducting wildlife research (see Box 1). The scientists gain experience with new species and habitats, network with others in their field, and sometimes use expedition data for their own research. Students from schools and universities, who fundraise to particpate in the expedition, gain valuable training and experience.

Scientists and students have recently been investigating hunting and attitudes towards wildlife with the locals. This is in search of an answer to a difficult question- how to sustain the 20 000 people living in the area without overexploiting the forest. The pressure from climate change is pushing wildlife deeper into conflict with locals, calling for an urgent shift in strategy to protect the reserve’s fauna. But driving change in the local lifestyle is complicated by cultural and economic barriers.

A key strategy to tackle this problem is to involve locals in the expedition. Mexican guides from local communities (.) are employed as para-biologists. The Maya’s deep knowledge of the jungle is invaluable to the data collection effort. Many can immediately identify hundreds of animal or plant species from sight, track or sound. Such skill would take foreign scientists years to master. Employing locals as guides, cooks, and logistics staff provides them with income whilst exposing them to the opinions and work of passionate conservationists. This cultural exchange can boost locals’ pride in the natural wealth of their reserve.

Local Mayan guide and ex-hunter Don Nicolas in the forests near Mancolona. Don Nicolas was highly respected amongst the mammal team for his tracking skills.

Local tracking guide Felipe takes a shortcut through a milpa to reach the Dos Naciones township after hiking a mammal transect.

Assisted by a government agency, the National Commission of Protected Natural Areas (CONANP), Calakmul’s people are becoming more environmentally-aware and active stewards of their forests. Outside of OpWall’s field season, many of the expedition’s local staff work in ecotourism.

Watching workers plant saplings in patches of regenerating forest near the Hormiguero campsite, I ask our Mayan tracking guide Don Victor () if they’re growing coffee or chocolate. To my surprise, he tells me proudly that it’s Ramon or breadnut tree (Brosimum alicastrum). Ramon makes up the bulk of the forest here, and its fruit is an important food source to wildlife such as deer and peccary. They’re not growing crops, but reforesting the site of an old milpa, and in return receiving government payments for environmental services. Further into the jungle, Don Victor points out small concrete troughs on the forest floor. He explains his community has built and placed eighty of them in the area as water receptacles, so that animals don’t leave the reserve in times of drought. Dozens of treefrog tadpoles wriggle in the rainwater already accumulated inside.

Mayan ex-hunter Don Victor, from the Hormiguero community, was employed as a tree identification and mammal tracking guide.

There is a great effort to save water for wildlife. Some of the camera traps reveal animal activity around large black tubs that act as artificial aguadas to catch rainwater, preventing it from disappearing into the porous soil. Flicking through the images, I watch the students’ fascinated faces as animal after animal visits these dependable water reservoirs. Herons fish for frogs, deer sneak a sip just minutes after a thirsty jaguar has prowled through, and tapir wander by in the night to drink their fill. The future often seems bleak for Latin America’s wildlife, but these sights fill me with hope. Finally in October, a few months after the expedition, heavy rain refilled all of the reserve’s aguadas – giving wildlife a second chance for the near future. Even if drought strikes again, maybe hard work and ingenuity will keep Calakmul one-step ahead of climate change.

BOX 1– Conservation research methods used in Calakmul

Butterfly traps – in this case, humane upside-down cylinders of mosquito netting suspended from a tree. The traps are baited with rotting banana on a plate just below the netting; as butterflies take off vertically, most are caught in the cylinder when they try to leave.

Camera trap – camera attached to a fixed structure (such as a tree), in which an infrared sensor is triggered by movement to capture images of animals frequenting the area.

Mist net – fine mesh lightweight net, often made of natural biodegradable material, which is difficult to see at a distance. These are stretched out at strategic points to capture flying animals without injuring them

Point count – audio survey where observers listen to and identify bird calls at the dawn chorus in a fixed location for a set period of time.

Visual encounter transects – survey transects in which observers search for and record species they see and identify.

Transects – a pre-determined line along which data is collected continuously or at set distances.

Scientists and guides lead daily surveys collecting data on specific taxa, with students acting as research assistants. For herpetofauna (amphibians and reptiles), visual encounter transects are conducted along the forest trails and around aguadas (. Mammal transect teams search for tracks and spot troops of monkeys, supported by analysis of images from camera traps spread in a grid throughout the reserve . After dark, mist nets are deployed by bat survey teams (). Bird survey teams set their nets in the in the early morning () and carry out point counts: stationary surveys of bird calls conducted at the dawn chorus. , a new project trialled butterfly traps at two of the campsites. Habitat surveys identify ( and measure the circumference of trees in quadrats next to transects. Combined with measurements of forest structure, these data help understand how animal species distribution relates to the jungle’s architecture. Annual surveys in the same locations enable year-on-year comparisons, which in turn can be linked to environmental conditions such as rainfall or temperature.

. Sunset at the Mancolona campsite [Suggested background image for centerspread]

Herpetologist Jose (Portugal), one of the expedition leaders, with a juvenile Morelet’s crocodile (Crocodylus moreletii) caught at an aguada. The string was attached to a pessola in order to weigh the animal. While on expedition, Jose also conducts field research on this species for his PhD thesis.

. Herpetologists hold a brace of white-lipped mud turtles (Kinosternon leucostomum) caught in quick succession on a nocturnal aguada survey. Aguadas are often home to high densities of amphibians and reptiles. Catching amphibians and reptiles allows proper identification and body measurements to be taken.

. Chiropterologist Evie, from Oxford, carefully works to free a bat from a mist net.

A bat’s forearm bone is measured using a high-precision calliper. Hair length, colour, and facial characteristics identify families of bats, but forearm measurements help to distinguish closely-related species with similar morphology.

Ornithologist Carmen (Portugal) supervises camp manager and biologist Samuel (UK) as he learns to free birds from a mist net. Working with scientists from different fields is a unique opportunity to learn research skills specific to the taxa they study.

An ornithologist carefully examines a hummingbird to identify it. Because of hummingbirds’ small size and fast metabolism, they have to be handled with different grips to larger birds, and must be processed quickly or fed sugar solution to avoid their body temperature dropping rapidly.

Ornithologist Carmen, from Portugal, holds a blue bunting (Cyanocompsa parellina) caught in a mist net near an aguada

Butterfly scientist Chris (Canada) records data as local Mayan guide Don Victor identifies the species of each tree in the area surrounding a set of butterfly traps.

Terms explained

– ponds or small lakes filled entirely by rainwater. These are often seasonal or semi-permanent, and may dry up entirely when rainfall is low.

Behavioural adaptation – when a species changes its behaviour to maximise fitness in response to an environmental stressor, as opposed to genetic adaptation via natural selection.

Biosphere reserve – a large wilderness area of pristine habitat designated by a national government, created to work on compromises between conservation and the use of biodiversity for human livelihoods.

Buffer zone – land at the edges of the reserve surrounding the core zone. This is often used by humans for purposes which conform with ecological and conservation practices.

Core zone – the central part of the reserve away from its edges which is strictly protected for conservation purposes. The core zone is often least affected by outside human influence, as it is protected by the buffer zone.

Currassow – large terrestrial bird.

Mayan tracking guides – local people from indigenous communities employed to assist mammal scientists in finding and identifying animal tracks.

Milpa – traditional small-scale Mayan crop field grown for several years on land cleared by slash-and-burn, before being abandoned as the farmers move on to new land.

Ocelot – medium-sized wild cat native to Latin America.

Paca – large rodent native to Latin America.

Para-biologists – local people without a university education nonetheless employed and trained to work as guides, scientists or research assistants.

IUCN Red List – the most comprehensive list of species’ conservation statuses, evaluated based on their risk of extinction. The list is compiled by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the main international authority which classifies species as Least Concern, Vulnerable, Endangered, etc.

Transects – a pre-determined line along which data is collected continuously or at set distances.

Transition area – land outside the buffer zone which is used for sustainable human and economic development.

Acknowledgements:

The author is grateful to Dr. Kathy Slater, José António Nóbrega and Molly Crookshank for their input and scientific information, both in the field and during editing. Thanks are also extended to Liz Sheffield and Liz Jensen for their editorial input.

Author:

Raphaël Coleman is a Zoology graduate from the University of Manchester. He works on conservation projects around the world, connecting passionate nature protectors through the Wildwork – the online Network of Wildlife and Wilderness Workers. You can follow their work on social media (@thewildwork), or on wildwork.net.

To learn more, visit the following resources:

A short film about the project, shot on the 2017 expedition:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T4kFL5eb10M

http://opwall.com/research-objectives/mexico/

file:///D:/Downloads/Documents/OPERATION-WALLACEA-2013-FIELD-SEASON-REPORT.pdf

Further reading (academic):

IUCN Red Listing for Baird’s Tapir:

http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/biblio/21471/0

Peccary ranging patterns and water availability – Reyna-Hurtado et al. 2009: http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1644/08-MAMM-A-246.1?journalCode=mamm

Mammal presence in hunted and non-hunted areas – Reyna-Hurtado & Tanner, 2005:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-7429.2005.00086.x/full

Schools and undergraduate students can apply to join the Mexico expedition at:

http://opwall.com/undergrad-research-assistants/locations/mexico/